The following conversation was conducted as a public event at Jennifer Terzian Gallery on September 18, 2022. It has been edited slightly here for clarity and brevity.

Keely Orgeman: The show consists of two series: one from 2022, and the other from 2012. The two series share the same title which is…

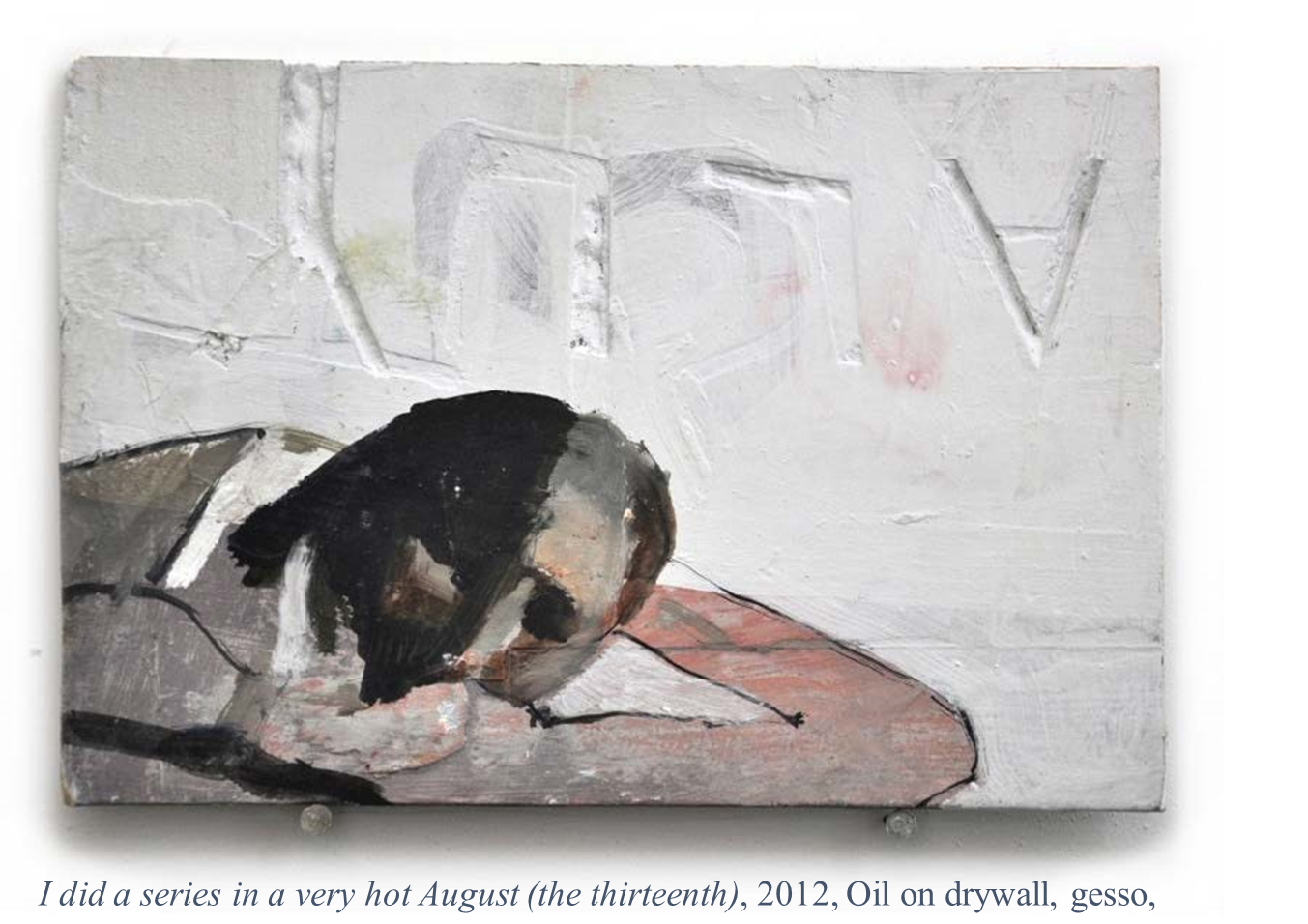

Julia Rooney: “I did a series in a very hot august,” which is the title of a poem by Anne Marie Rooney, who is my sister and is a poet. The 2012 series took on this title when I made it, and then in the coming of this show, I decided to name the new body of work along the same lines.

KO: Could you tell us a little bit about why you chose this title, what meaning it has for you, and why you’ve used it for both series?

JR: I was rereading the poem this morning. The way that it is printed on the page always struck me as not being a linear piece of text. There are two columns, and you can read the piece across from left to right, or you can read one column first, and then the other. As a structure this intrigued me—that there is not one way to read this text. Also, it may be interpreted by the person reading the page differently than by the speaker. So, if you were to hear this poem read aloud, it could be one way, and if you would see it on a page, it would invite other forms of reading. This was a compelling idea to me when thinking about the paintings: that the spatial organization of them is key.

When Jennifer and I were talking about doing this show, I knew that I wanted to have a contemporary body of work to complement the older one related to the same ideas of scale, the screen—and I liked the idea that the series would be exactly the same in name except for its date. I was thinking about the way that technology upgrades itself and yet it’s still the same device, it’s just a new generation. Also, the idea of a series: there are many pieces within each body of work, but then there can also be many bodies of work. So, if I were to do another series in another ten years, it would perhaps bear the same title but have another date.

KO: As an art historian, I of course read too much into the title. When it says, “I did a series in a very hot August” I assumed that you were thinking of the embodied, physical experience of making work, laboring over work, over and over again in this repetitious way, in this very discreet moment in time, and that’s what you were trying to signal through that title. But that sounds way off—I’ll throw out that interpretation! With the earlier series, you mentioned to me that at the time you were beginning to consider architecture in relation to your work. I wonder if you’d talk about the progression from 2012 to now in terms of your responsiveness to architecture—not just in terms of your paintings, but in terms of the installation.

JR: The 2012 paintings came about after having spent a few summers in Italy doing research and writing work. That was the first time I felt really moved by seeing painting that was inextricably embedded in an environment—in religious spaces (churches), but also in ruins, as in the frescos from Pompeii and Herculaneum. I began thinking about painting as fundamentally having to do with a context, as opposed to painting as an object which is put on a wall—which is how we often experience objects in museums. So that was very much in the back of my mind in the 2008-2011 years. In making these pieces, I chose the substrate of Sheetrock thinking of them as having a relationship to the wall. I didn’t want them to be canvas which has a very contained edge and sets up its perimeters from the beginning. Sheetrock comes in a 4’ x 8’ panel—you score it, and it cracks. It’s a material that is on the one hand very durable—it holds up our walls— and on the other hand, it’s extremely easy to work with. It was important to me that these paintings existed on a substance that would otherwise be used in a domestic environment. It was Jennifer’s gallery that inspired this particular installation. The first time I came to the gallery, I was really struck by the symmetry of it—the two doors and the wainscotting. I think many galleries these days try to create the white cube—no architectural features that will distract from the experience of looking. I was really excited by the features that were so specific to this space, and excited about the idea of using the built-in architecture as a construct and a mounting strategy. Then I built in some shelves that emulated the original ones in the space.

KO: I was wondering if those were shelves you built into the wall.

JR: Yes, I really wanted these pieces to be specific to the gallery. Often, you don’t experience work in architecture these days. You experience it on a phone.

KO: That gives us a good understanding of your relationship to architecture as a foundation. Related to style, there are obviously two very different styles represented in these bodies of work. I have a quote here from an interview you gave last year in which you said, “In today’s world where the fact/fiction dichotomy is especially fraught, abstraction offers a third option that does not foreclose thought at the same time that it does not evade the messiness of debate.” Would you say that your earlier body of work operates by this logic of abstraction even though it is representational—that it operates somewhere between the imagined and the real?

JR: Yes, the first ones I made were extremely literal in a photographic sense. But as I worked, it became less and less relevant to remain true to a source. Rather, the material took over. Some have extremely pock-marked surfaces, and others have carved text in them. Those were old paintings that I cannibalized to turn into these new works. Also, the abundance of them became essential. Each one was stylistically different and they contradicted each other. It’s the combination of all of them together that is the work. I don’t see each one as a single piece, but rather as a body of work. The contradiction within them is essential to their form.

JR: Yes, the first ones I made were extremely literal in a photographic sense. But as I worked, it became less and less relevant to remain true to a source. Rather, the material took over. Some have extremely pock-marked surfaces, and others have carved text in them. Those were old paintings that I cannibalized to turn into these new works. Also, the abundance of them became essential. Each one was stylistically different and they contradicted each other. It’s the combination of all of them together that is the work. I don’t see each one as a single piece, but rather as a body of work. The contradiction within them is essential to their form.

KO: This raises a question for me. How do you feel about some of these works from the series being pulled apart— in different collections if they’re sold?

JR: I’m ok with that. I think about many artists’ work being spackle and plaster, 9 in x 13 in. divided into various collections, and then at points they come together for a show.

KO: Why and when did you make this stylistic shift from representation to something that we recognize as more fully abstract with your new series?

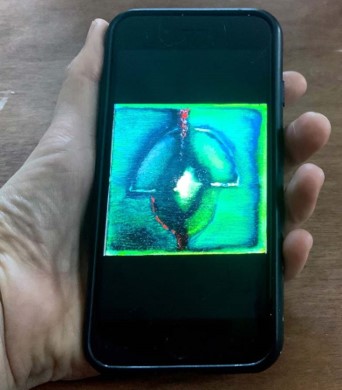

JR: I started working abstractly in 2014 and have pretty much been on that train since then. But I would say these paintings operate on two different levels of abstraction. There’s the abstract imagery within, but then there’s the object that’s so clearly related to something we do recognize—the phone. I feel that what’s essential to these two bodies of work is not so much the imagery contained within, but formally the shape and size of these two structures which are both very literal.

KO: The iPhone is the reference in the 2022 work. What’s the literal reference in the 2012 works?

JR: The literal reference is a laptop. They were shot on a laptop by a laptop—so I consider the laptop to be the DNA or the author of the source imagery. It’s the idea that they came from a screen and that they are then born again as these screen-like things. It was also very important to me that they had this suggestion of tactility, in terms of not being framed. I’ve only ever exhibited them propped so that you could think about them as objects—like a tablet or a laptop.

KO: Movable, portable.

JR: It’s interesting to me that this phone device would be recognizable to our eyes—as a contemporary audience—but that it might not be in 50 years. It will probably be an extinct technology, so it does in a way become a marker of the moment in which it was created.

KO: There is some period specificity in these works.

JR: Yes.

KO: I have a number of questions related to scale—the first of which is: was this series the first time you used scale as a conceptual and physical framework for your work?

JR: Yes, it was. But it wasn’t evident to me that it was until I was halfway into it.

KO: I know that you’ve done both extremes, large and small-scale work. Why small again now?

JR: I started making really small paintings (2-inch x 2-inch) in 2020—before the pandemic, though I exhibited them at Arts+Leisure Gallery in New York during the height of the pandemic. I was thinking about phones as these spaces that we are almost always looking at the world through. Whether it’s art, or it’s life, so much of our existence is mediated by the screen. I started a series of 2-inch paintings which I always envisioned as having these dual existences: 1) the way they would be seen on a phone, and 2) the way they would be felt in a gallery…and knowing that those two experiences would be very different, but that if you didn’t see both, you wouldn’t feel the rift between them. That series was specifically about Instagram, but my interest in scale was the formal crux of my thinking. I was also making these 6-foot paintings and interested in exhibiting the 6-foot and the 2-inch paintings side by side. What does this distance actually feel like, physically?

KO: And yet those two different size paintings look exactly the same size when represented on Instagram. They’re all roughly two inches. Getting deeper into the scale idea, can you get into what you think are the social consequences— the psychological consequences—of the fact that most people view works of art now and consume them through the screen, which miniaturizes them all to the same scale and completely distorts the physical size of the object? Can you get at what that does to us?

JR: This past year as a CT Doran Artist-in-Residence, a lot of my research focused on how the architecture of these websites is designed. My artistic focus started as a scale issue—in the idea that we’re completely losing the scope of what these things mean in the world. Politics, information, etc.—social media distorts our understanding of ourselves and our realities. The things I’ve become more concerned about are the ways these algorithms feed us information. What you see on your feed is curated by a machine, and that’s been designed by a person, and often the people who are designing those have very specific interests that are capitalistically-driven. So, I think about it with regards to art: who are you being exposed to? Why are you being exposed to these artists? And how is that different from going to someone’s studio and actually seeing what’s there? I want to go to people’s studios, I want to go to museums, I really don’t want to see what people decide to post online. On the other hand, I know it’s a really great way to share events, but I also think it’s changing the way people look at art, what art people make, what gets shown, what gets bought, how the market is shifting in accordance to popularity and liking. All of these things are very different from making. It’s something that I have struggled deeply with for the past two years, and am still trying to figure out my relationship to. I feel like I have to participate in some way, but not completely give into it. I talk to a lot of artists about this, and it’s not like I’ve figured out an answer.

KO: Yes, you’re stuck in the same loop.

JR: And I wonder for you as a curator, how your relationship to discovering and looking at artists is informed by this. I think it’s very different for someone looking at art than making art.

KO: Yes, it was very tough during the pandemic as a curator to rely so much on digital media to really understand what was still happening in the art world rather than visiting museums and galleries myself. I live at Yale and I work at Yale so we were really controlled and limited in what we could do during the pandemic. We were not supposed to be traveling. I felt doubly responsible for staying put, and that made me more reliant than ever for the first time on consuming what artists were putting out digitally and paying attention to that. I’m not much of an Instagram poster, but I consume a lot of artists’ work digitally. But now that I’m getting out in the world again and travelling, I’m still trying to hold myself accountable to the standard of seeing works of art firsthand. I do that as often as I can. It’s very important to me. That’s how I was trained as a curator, and even going back before I knew art history existed as a discipline, I was always connected to making and really experiencing the materiality of art. So it’s good practice to not buy based on what you see on the screen, but to go to places and look. How would you say your work addresses this tension between these two types of viewing experiences? The physical and the digital?

JR: My interest in the 2022 works is with how I photograph them. The way I want them to be documented and posted on Instagram for instance—I only want to post the painted area, not the multiple frames around it, because on a phone, the thing that’s most seductive about them is the painted part. I like the idea that they become this immersive image on one’s phone. The painted images are not representational, but I was thinking a lot about globes, eyes, orbs, celestial bodies. When you think about looking at the sky—you see the stars and you know that they’re massive, but you see them as blips. That is the most extreme scale shift we experience every day. I was also thinking a lot about eyes—they’re a physical form, but they’re also a hole that allows light to come in. It has the duality of being a positive and a negative form. The eyes see, but we can also see them. How do we see? What do we see? Why do we see what we see? That’s very philosophical but it is something I think about a lot. Why is the way I see something the way I see it, and how do phones and computer screens and algorithms condition what we see and start to change how we think and act as a result? My reading about these companies makes me think that they do not have humanity at heart. I think they’re quite dangerous.

KO: What you just said made me think that the references—subtle as they are to orbs, to eyes, to lenses—really call attention to the act of seeing, of viewing, of looking, in the same way that the frames also call attention to the visual device of framing that is so constant in the digital world. There is the white or black negative space around the painted image, but then you have the negative space of the gray mount, and the further negative space of the white or black borders. They’re frames within frames. Did you intend to use the frames in this installation as a way of fixing these images in a place and time—fixing them in the sense that they’re no longer these mobile objects that we’re carrying with us, that they’re on a wall, in a place–or are you thinking of them differently for this installation?

JR: For this register of paintings, I was thinking about the body moving across the room and the rhythm created by the black/white, horizontal/vertical sequence. I wasn’t thinking about the objects as being mobile, but about our bodies as being mobile: what is the experience of being in a gallery and having to move your body from left to right to see the work. For me, being in a gallery is always about reading many things at once—to have your peripheral vision be part of your central vision. So I was thinking about the frames as creating a rhythm, and not having a regular pattern. I wanted there to be this syncopation. On the one hand they’re very monotonous—the same boring square—but they’re actually not logical in the way they’re hung. I was thinking about the body and…

KO: Compelled to go from one to the other?

JR: Yes. I was in the Yale Art Gallery this afternoon and I was thinking about the rehanging of a lot of paintings that I recognized but I hadn’t seen for a couple of months, and it really made a difference to see them in a different space and in the context of new work. That’s always a question I have for you and how you think about that when you decide what goes up and what goes next to what.

KO: That context is everything. The relationships that I put together as a curator, the relationship between works of art— that is always at the forefront of my mind. Whether it is a pairing or a grouping of objects, I am thinking about what those relationships are. Discreet relationships that can spark ideas, conversations. I reinstalled the Modern and European galleries recently and it was all about what you see within the same site line. I love what you just said about peripheral vision being part of the experience as much as it is about the central vision when you’re in a museum or a gallery. That’s so true—it’s the atmosphere that is contributing information to you as you are viewing a work of art. It’s information, it’s smell, it’s people. It’s all part of the physical experience, which you completely lose in just viewing the work of art on your phone. It gets rid of all that extraneous information, the materiality, the texture. Everything is gone.

JR: I think also about sequence. The act of scrolling is about going from top to bottom. It’s different on a computer where you can have many windows…I always have a million windows open! But on a phone, you’re on one page, you’re at the top or the bottom. In a gallery it doesn’t have that hierarchy.

KO: We’ve been talking about the central images in the 2022 works, and I wanted to relate this series to another recent series you made during the peak of the pandemic, where the painted forms emerged from your observations of the imperfections in the canvas, the warped sides. You drew the images from looking at those imperfections and I wonder if there’s any of that in these works.

JR: Yes. I feel like an artwork starts when you are preparing to make the artwork. Those artworks started when the stretcher bars cracked, and if I weren’t stretching them myself, I wouldn’t have noticed that or thought about it as potential material to work with. The 2022 paintings started with a pretext, which was the device and the very pixelated screenshots captured by that device. Also the Sheetrock surfaces were gnarly, and had other stuff on them—they were carved into and cracked. I’m thinking a lot about serendipity in this work, and how that differs from what is orchestrated or programmed in digital space. There is not the same ability to discover a thing hanging out in the corner. If it’s not put in front of you, you’re probably not going to find it. You’re not seeing the periphery. You’re not seeing all the trash. The trash is sometimes very interesting.

KO: I have two more questions for you. One is related to relationships. I noticed that with a lot of your work, you’re working in collaboration with someone—your sister or your fellow artists. The 2012 series came from a breakup. You were in a long-distance relationship and the images are drawn from the set of screenshots you received after you broke up. What relationships might you be addressing? Maybe they’re not people you know, but what relationships might you be addressing in this new body of work, and why have you decided to manifest these social connections in material form?

KO: I have two more questions for you. One is related to relationships. I noticed that with a lot of your work, you’re working in collaboration with someone—your sister or your fellow artists. The 2012 series came from a breakup. You were in a long-distance relationship and the images are drawn from the set of screenshots you received after you broke up. What relationships might you be addressing? Maybe they’re not people you know, but what relationships might you be addressing in this new body of work, and why have you decided to manifest these social connections in material form?

JR: I think painting can be a pretty isolating endeavor, and I love that about it. But I have always thought about paintings as having a social life. And my hope for paintings is that they do exist in a social capacity—in the sense that they change as they enter the world. They change as they are put into I did a series in a very hot August (the first), 2012, Oil on drywall, gesso, gallery spaces, or as they are put into public spaces. I want spackle and plaster, 9 in x 13 in my paintings to invite some kind of connection that is not passive. I bring it back to Italy—my experiences of being in spaces where paintings really had a social function. These paintings were made in churches to teach certain religious stories and they had tremendous power. That’s stuck with me all these years. Also, at the time of making the 2012 series, I was working at the Met. On my lunch break I would go into the galleries and walk around, and one day I came across these portraits produced in Roman Egypt in the 2nd century AD. They were called Fayum portraits, and were made with encaustic on wood. They were unbelievably luminous paintings of people’s faces, and they had a function of commemorating a person’s life. Those really stuck with me—on the one hand they were amazing paintings technically– but also they were made with a function in mind, and those two qualities weren’t at odds with each other. That was on my mind in a very deep way, that paintings should have social lives.

KO: You told me that while these are autobiographical–they clearly depict you at different moments—that it’s not really important to you that they’re about you. Did you also say they helped you to process something, to process a loss in some way? I thought about that in what you said to me about the 2022 paintings about what loss is visible here, or felt here. How rare it is to have this experience of being together and looking at art—and there seems to be for me when I look at these works a sense of what’s been lost through the digital experience.

I want to conclude with another social dimension of your work. In a recent interview, you said: “Experiencing an object physically in front of you will always be different than experiencing an object through a screen.” That seems true. But can you say whether your paintings make a statement of value about experiencing works of art firsthand in a physical and embodied way?

JR: I personally have an opinion about that. I think it’s always better to experience things in person. But I would hope that the paintings invite people to consider that question for themselves, because I don’t think it’s an inherent conclusion for everybody. It’s often very hard to see things in person depending on where you live. So as an artist, I don’t want my paintings to be didactic—to say this is the “right way” to see them, but rather to prompt the question: what is it for me to see this thing on a phone, and what is it for me to see this thing in space? Is there a difference? Is that difference important to me? And how am I going to move forward? That’s what I think art should do: rather than telling people anything specifically, it should invite people to consider for themselves how they want to situate themselves in the world.