BY TRACEY O’SHAUGHNESSY REPUBLICAN-AMERICAN

In the sooty, smoking aftermath of World War II, the august churches of western France smoldered in a fog of charcoal rubble. Shards of stained glass – the French answer to Italian frescoes – lay shattered and strewn about like broken beer bottles.

The structures themselves – soaring vitrines, arcing buttresses, and thickets of rib vaults – sat exposed and jagged, their vast domes open to the exposed heavens, the innovative verticality of centuries sundered by the ingenious weaponry of the 20th century.

That sense of chaos, violence and confusion is at the center of Brendan John Carroll’s “Ancient Modern Future,” at Litchfield’s Jennifer Terzian Gallery through Jan. 20.

Carroll is a devout Abstract Expressionist whose pantheon includes de Kooning and Kline, Pollock and Marden. He is also a cradle Catholic who has wrestled with his faith, magnetized by its beauty and nettled by its failings.

His work is an incarnation of that ambivalence, a furious internal warfare spoken in the abstract expressionist language in which he is as fluent as he is faithful.

His paintings, like his attitude toward religion, are deeply layered and torn, glossed over and patched together, furious and tender. Executed in vivid, exclamatory colors, they resemble stained glass windows, albeit ones that have been shattered and clumsily reassembled, a bit like faith itself.

In “Stones for Goliath,” for example, rhythmic lashing lines of deep violet and inky black thread through pickets of citrus yellow and juicy orange. In between, pools of filmy cerulean blue, spread like patches of sky. Carroll plays with an explosive energy articulated in penitential purple against contemporary, comic-book-like, in a way that suggests irony laced with longing. Those ponds of blue are epoxy, which Carroll layers on a canvas saturated with acrylic. He then encases the canvas with thick layers of tape, over which he brushes thick, clotty strokes of oil paint.

The process of making the art is one of building up and tearing away, a bit like Carroll’s own spiritual narrative. He proceeds to rip, tear and slash – effectively vandalize – his canvas, revealing passages of pellucid color – tangerine orange, charcoal gray, canary yellow that offer sanctuaries of tranquility in an otherwise savage engagement.

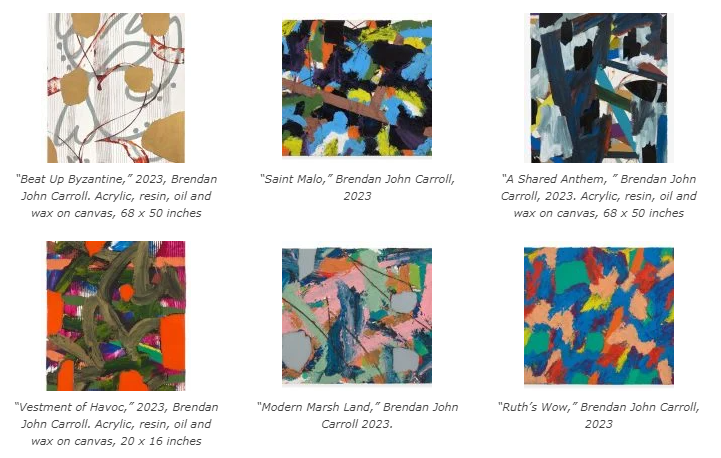

A work like “Beat Up Byzantine,” among Carroll’s more restrained work, features eddies of golden patches, lightly strung together with calligraphic, blood-red coils. Others, like the impassioned “A Shared Anthem,” quake with thickly painted midnight blue pickets that slice through flurries of powder blue.

Throughout these works, Carroll creates a sense of architectural latticework that’s been ravaged or toppled, large shafts of color severed from their proper place. A slicing coppery plank slices through the blue and red eddies in “Saint Malo.” Slender apricot slabs pierce through lyrical swarms of tomato red and saffron. Something has been lost, disturbed, or defaced in these suggestive images, but that wreckage has a beauty all its own.

“Sometimes the damage that’s been done to something may be a beautiful object on its own,” he said.

Carroll said that his images address the two veins of his life that are important to him: Religion and art. He remembers the sensual uplift he felt entering the sublime Gothic churches of Europe. It felt like the exhilaration he experienced looking at the work of first-generation Abstract Expressionists, like de Kooning.

“These stories and questions of what’s illuminated on those giant Gothic cathedrals – where do we come from, what is the meaning of life, what’s it supposed to matter, where are we going? These are the questions that are addressed in some of those Old and New Testament images on the Gothic cathedrals are the same questions people like Barnett Newman or Rothko were asking,” he said. “These are things for which I have my own questions. There have been times when they have felt frustrating and painful.”

In works like “Vestment of Havoc,” in which iridescent, serpentine green strokes slither and snake through geometric passages of rich vermillion, that sense of upset takes vivid form. It’s a disfigurement of primal beauty, that nevertheless creates its own shimmering grandeur.

What: Brendan John Carroll “Ancient Modern Future.”

Where: Jennifer Terzian Gallery, 3 South St, Litchfield

When: Through Jan. 20