BY TRACEY O’SHAUGHNESSY REPUBLICAN-AMERICAN

March 24, 2022

Artist Richard Pasquarelli had always been an organized person – a little too organized for his family, who often wondered why he had to have certain objects in specific places all the time.

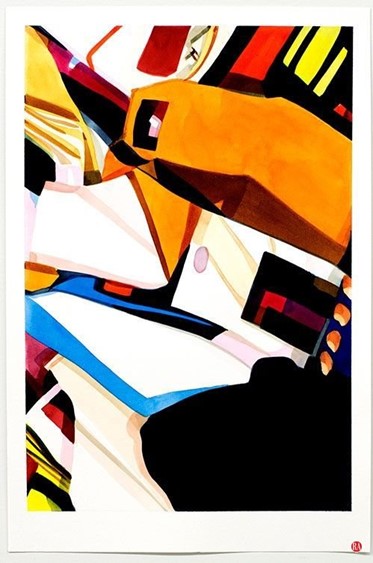

In a new exhibit at the Jennifer Terzian Gallery in Litchfield, Pasquarelli reveals the fruits of his immersion into the fields of obsessive compulsive disorder and hoarding disorder. The paintings are colorful, abstracted works that explore the relationship of physical reality and the mind.

In an email interview, Pasquarelli said the idea came to him because “I am organizationally obsessive compulsive. I notice every scuff, crack and dent. I constantly move objects back into their correct positions.”

He said he began asking himself “why do I have to do this?” It was a process that led him to research in mental health, psychology, physical sciences and philosophy.

“I started to see the world around us as a physical manifestation, or extension of our psyches,” he said. “I wanted to further this research and decided to go into the field to find observable evidence of these relationships.”

His paintings, often vividly painted flat, geometric forms, make visible the relationships between physical reality and the mind. Pasquarelli said his research helped him better understand the relationships between mind and matter and their presence in the world around us.

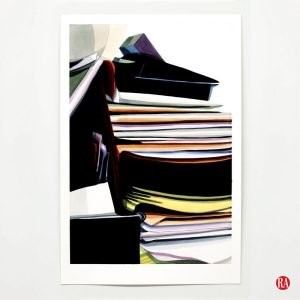

He said hoarding disorder intrigued him “because it was also a condition that centered around people’s relationships to ‘ things,’ but with antithetical behavior to my own.” He later attended a conference on hoarding and learned that more than 90% of those affected by it had suffered a traumatic event in their childhood.

“Now, when I go into these environments, I often picture them as a child, and this stirs a sense of empathy within me. What I learned has influenced the way that I see these environments, as I consider the ways the subconscious is evidenced in the objects people choose to live with,” he said.

About 2.6% of Americans wrestle with hoarding disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Society. Rates are higher for people over 60 years old and people with other psychiatric diagnoses, especially anxiety and depression. The condition appears to affect men and women equally, the group says.

Pasquarelli said he met a woman, Barta, at a hoarding conference. She later invited the artist to her home.

“During my visit, she told me stories of traumatic events from her childhood, and I noticed the way in which she told me those stories,” he said. “She was very precise in her descriptions of the details: dates, times, the age she was, and the places in which these events occurred. When I looked around her home, I saw how, in essence, her hoard was her ‘proof’ of this past. When I created paintings based on her environment, I was less concerned with depicting what the objects were but rather more interested in representing their overall physical presence. I seek to capture that.“

Pasquarelli, whose colors can recall the work of Stuart Davis, said he has been inspired by artists like Matisse, James Rosenquist and Ellsworth Kelly. “I don’t blend colors to create volume,” he said. “Instead, I use flat colors of different hues next to one another, which not only forms volume but produces an abstraction to my work.”

This gives what might otherwise be seen as piles of “stuff” a sense of formality, order and vividness.

Pasquarelli lives and works in New York City but is a part-time Bantam resident. He has exhibited his work in solo and group exhibitions in museums, galleries and art fairs throughout the U.S. and Europe. His work is represented globally in many public and private collections, including the Library of Congress, Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts and the Beth Rudin DeWoody collection.

IF YOU GO

The Jennifer Terzian Gallery is at 3 South St., Litchfield. The exhibit will continue through April 2. For information, visit jenniferterziangallery.com, call 714-932-5497 or email info@jenniferterziangallery.com.